Finals roll around, and it can go one of two ways…

1. They go smoothly or

2. You end up pulling your hair out

Either you have already studied throughout the semester and know the material, or you have not studied and have to cram it in all in the night before.

Both scenarios stem from the habits you took throughout the semester. Obviously, anyone would look at this and say, “Duh! Either they studied, or they didn’t.” However, throughout your daily life, approximately 40% of your behaviors are habits (Neal, Wood, & Quinn 2006). The successful student have successful habits, and the unsuccessful student have habits which sets them up for failure.

Some habits include…

- – Waking up at 8 am and hitting the snooze 3 times before you wake up

- – Watching TV after class

- – Going to the gym or going on a run after class

- – Going to class on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday at 12:30 pm

What is a habit?

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a habit is “a settled tendency or usual manner of behavior.” So, every repeated task, behavior, and tendency are habits.

Most people wouldn’t think of hitting a light switch every time they walk into a room as a habit. Of course, they need to see, so they turn on the light. But, think about when they leave the room. They don’t have to turn off the light, yet some people tend to turn off the light and some tend to leave it on. Turning the light on and turning the light off is a “settled tendency or usual manner of behavior.”

So, let’s go back to the final exams scenarios and compare the habits of a successful student with the habits of an unsuccessful student.

Successful Student | Unsuccessful Student |

Goes to class | Skips class regularly |

Reads textbook | Relies on the lecture |

Asks for help | Works alone |

Gets work done ahead of time | Waits until the last minute to do work |

Limits distractions | Studies with phone next to them |

Goes to the library | Studies in a social environment |

Eats well | Eats fried chicken regularly |

Takes notes in class | Relies on their memory |

Of course, we can’t ignore the rest of college life. College students have a wide range of activities outside of academics, such as socializing, participating in clubs, eating, sleeping (or the lack of it), doing chores, exercising (or the lack of it), escapading on those weekend events

Often, students work hard in one area and lack in all others. They might be the most studious person around, yet they have little social life. On the flip side, they might go hard every night with their social life, yet their GPA drops every semester.

Bad habits lead to failure

The book, Habitudes by Tim Elmore, illustrates a metaphor for the necessity of habits. Imagine a bakery. Customers flock in and out of doors from opening to closing. The bakery grew in popularity because of the expert skills of the owner. He works tirelessly to create the most pristine baked goods around. From day to night, he preps, bakes, sells, talks to customers, closes for the day, cleans, and keeps the books (Elmore 2012). Knowing how many tasks lye on his plate, do you think he can maintain that work for long?

Of course, he can’t maintain it. He puts so much energy into the business and no time into himself. He desperately needs to eat, rest, and sleep. Ironically, he bakes food for a living yet forgets and neglects to feed himself.

Eventually, his thriving bakery slows down. Customers stopped showing up because the quality of pastries went down, the time to receive an order slowed down, and the energy the baker once had slowly dwindled. The baker was burnt out. He could not serve his customers because he forgot and neglected to serve himself.

As a student and a leader, do you stack task after task, event after event, class after class, and responsibility after responsibility? Is it likely you are running close to a burnout or are even burnt out at this very moment?

Managing and avoiding burnout is precisely why habits have so much value. Building the right habits keep you from running into the ground. Habits give people energy to keep up with consistent activity. Habits optimize productivity to give you back time and energy.

Reflection Question

Do you forget and neglect yourself?

Shortly, you will learn how to create hundreds of habits that will simplify your life. Before this happens, you must commit. Habits are created over time and eventually become a natural tendency. Once they begin to form, the habit will be performed effortlessly. But, it requires discipline.

Can you commit to the consistent effort in the pursuit of creating ease and endless possibilities? Be honest. If the answer is yes, the future awaits.

If you can’t commit, do yourself a favor. Stop reading, open a bakery, work 24/7/365, make a disgusting amount of money, buy a Ferrari, buy a lion-like Mike Tyson, overwork yourself, file bankruptcy, and come back to this same spot.

—- Here is a place holder for 10 years from now, so you can pick up reading where you left off. —-

Habits aren't complicated

MIT researchers broke down the human psychological reasoning behind all habits (1999). They made it three easy steps revolving in a process of a cue, a routine, and a reward. The habit loop gives rationale to why people perform their habits and insights to how to create new ones.Apply the loop to a common harmful habit. Using this process, you can analyze current behaviors, find the reason that it is performed, and replace it with a different, more positive habit. The following scenario and process were inspired by The Power of Habit written by Charles Duhigg. The scenario has been adapted to mimic a typical college habit.

MIT researchers broke down the human psychological reasoning behind all habits (1999). They made it three easy steps revolving in a process of a cue, a routine, and a reward. The habit loop gives rationale to why people perform their habits and insights to how to create new ones.Apply the loop to a common harmful habit. Using this process, you can analyze current behaviors, find the reason that it is performed, and replace it with a different, more positive habit. The following scenario and process were inspired by The Power of Habit written by Charles Duhigg. The scenario has been adapted to mimic a typical college habit.

Take into consideration a habit that negatively affects someone’s concentration. Amy, the hypothetical student, has a phone problem. While the professor recites their lecture, Amy repeatedly fidgets and gets distracted. The primary distraction, like many students, is her phone. When Amy arrives to class, she checks her phone, and to prevent herself from using the phone again, she puts it in her pocket. Like any other day, she listens and writes notes from the lecture, eventually grabbing the phone out of instinct.

What is the cue? What is the routine? What is the reward?

Step 1 - Identify the routine

The easiest one to identify is always the routine. The routine always is the observable behavior, aka the habit. In this case, grabbing her phone is the observable behavior.

- – Cue

- – Routine – Grabbing the phone

- – Reward

Step 2 - Experiment with rewards

Next, Amy tries out new alternatives to grabbing her phone. When she gets the urge to take out her phone, she does something else, anything else. She wanted to grab her phone and instead left the classroom to use the bathroom. She felt the urge to reach for her phone and instead drew a picture on her notes. She again felt the urge and instead took a drink from her water bottle.

Amy tries to discover a reward that satisfies her craving to reach for her phone. You might say the urge is unmistakable. It could be the urge to stay connected with her friends, maybe her FOMO is acting up, she might just need to fidget like usual.

Those are possible rewards, yet Amy won’t know for sure unless she follows this process. After every new reward she experiments with, she will immediately jot down the first three things that come to mind. Duhigg says it could be “emotions, random thoughts, reflections on how you’re feeling, or just the first three words that pop into your head”.

After she writes down her thoughts, she waits a couple of minutes. Duhigg recommends 15 minutes, but in this case, time is limited, so she waits 5 minutes.

If she still feels the urge to reach for her phone, she needs to do the process again. In her case, she didn’t feel the urge to reach for her phone after she went to the bathroom. Through her “three thought notes,” she hypothesized that the reward was a break from class. So, she tried again with a different reward that satisfied the same craving. She walked a brief lap around the building. Still, she had no urge to reach for her phone.

Now she knows her presumption was right, and she simply needed a break from focusing on the class lecture.

- – Cue

- – Routine – Grabbing the phone

- – Reward – Getting a mental break from class

Step 3 – Isolate the Cue

Much like the reward, a cue isn’t easy to identify. There are countless number of possible cues. One might seem obvious, but if you are wrong and stick with that assumption, this whole process is worthless. With the wrong cue, changing a habit is like riding a bicycle with no chain. When you identify the right cue, make sure to write your old habit a goodbye letter. You probably won’t miss it, anyway.

For your convenience, Duhigg has searched through the world of science and identified five categories of possible cues.

Location | Where are you? |

Time | What time is it? |

Emotional State | What’s your emotional state? |

Other People | Who else is around? |

Immediately Proceeding Action | What action came before the urge? |

During every urge and every occurrence of the habit, answer those questions.

Amy began her class lecture PSYC100, every MWF at 12:30 in Smith 140.

Amy answered the questions during her first urge. She was in Smith 140, it was 12:50, she felt confused, her friend was sitting to the left of her, and she was listening to the lecture of her class. She again felt the urge to get her phone and immediately wrote the answers to the question. She was in the same place, it was 1:12, she felt bored, she was still sitting next to her friend, and still in the god-awful lecture. Next instance of the habit. She wrote down the same information, except she now felt tired, confused, bored and it was 1:30.

First of all, it’s obvious she was in class (Smith 140), she sat next to her friend, and the lecture proceeded the routine every time. But Amy doesn’t think much of this data, because she experiences the same circumstances in another class in another lecture hall in the same building and she doesn’t check her phone every day. You might look at her emotional state and say that’s the cue. Obviously, she checked her phone when she was frustrated, bored, and/or tired, that’s the reason she needs the reward in the first place. You are right, but that’s not the whole picture.

The class started at 12:30, she picked up her phone at 12:50, then 1:12, and again at 1:30. On average, those times are about 20 minutes apart. From this data, Amy concludes she checks her phone about every 20 minutes. BINGO!

Finally, Amy has all the pieces of the puzzle and can move onto the final step, replacing the habit with a more productive one.

- – Cue – Checking her phone every 20 minutes

- – Routine – Grabbing the phone

- – Reward – Getting a mental break from class

Not all habits will occur frequently. Some habits occur once a day and, in some cases, they might occur every Monday during your internship, or every time you walk into your front door.

If they are less frequent, be patient. You might have less opportunity to experiment with rewards and less opportunity to reflect on cues.

Habits require discipline. Once again…

“It doesn’t take long to change a habit, but it’s hard. Really hard” – Peter Bregman

Time to Change Your Life

Here lays the cream of the crop… the golden buzzer… the A+ on a paper… the mountain peak… the caffeine to a late-night study… the professor that rounds up your grade… the paycheck to your empty bank account… the creation of endless habits aka, the life changer.

The opening paragraph to the entire post stated 40% of our daily behaviors are habits. It also said successful students have successful habits, and unsuccessful students have damaging habits.

In the successful vs. unsuccessful habits table instead. Students have 40% of their daily behaviors on autopilot. The table is set up to show the potential habit switches. One student could swap out eating fried chicken every day with eating a salad.

That swap works both ways. Someone could accidentally change a good habit into a bad one. When the semester catches up and people get stressed, they could potentially substitute taking a long nap after a stressful day instead of maintaining the routine of going to the gym.

40% doesn’t just signify the students, it represents everybody in the world.

If 40% of your daily behaviors are habits, and those habits are what make success, there is a huge opportunity to tap into that resource and leverage it in your favor. You can’t change all your habits, but you sure can change a good amount. Even changing one habit can have a meaningful impact on your life.

A list of 38 successful habits:

Meditate | Call Mom |

Call Dad | Don’t procrastinate |

Plan projects before you start | Take notes |

Review notes and rewrite notes | Go to class |

Get to class on time | Ask questions during class |

Get rid of all distractions while studying | Study in the library |

Eat breakfast | Eat three meals |

Drink 8 glasses of water | Eat vegetables |

Workout | Go to sleep at the same time every night |

Wake up at the same time every morning | Don’t hit snooze |

Morning routine | Nighttime routine |

Run | Stretch |

Save 10% of your paycheck | Apply for 2 scholarships a week |

Limit social media to 45 min a day | Bathe |

Brush teeth | Keep up hygiene |

Floss | Reflect on goals |

Read | Journal |

Take 10 photos a day | Draw 1 picture a day |

Write 750 words a day | Clean your room |

You have either

Identified a habit you want to replace and identified

or

You have skipped the first step and just identified a habit you want to create.

DO NOT SKIP STEPS!

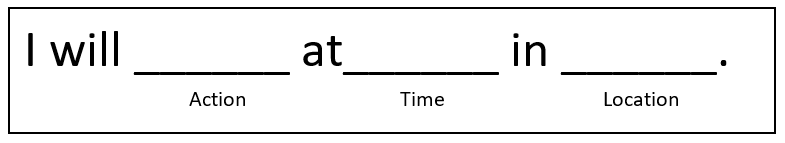

Step 4 – Have a plan

The prompt above is called an implementation intention from James Clear’s book, Atomic Habits.

Imagine Tim, who wants to start working out. Two days after going to the gym, Tim had an open block of time for 3 hours. After class, he went home and relaxed for a little bit. He relaxed so much that he blew off the gym and decided to work out tomorrow instead.

Tim could have benefited from an implementation intention. If he knew precisely what workout he was doing, what time and day he was doing it, and where he was doing it, he wouldn’t have blown off the habit.

Here is the process of creating an implementation intention

Get a specific action. What does workout mean? For Tim, that means lift weights for each main muscle group. Each workout will also consist of a 15-minute cooldown on the treadmill. Without this much detail, he could easily go to the gym for 30 minutes, throw around any type of weight, and call that a success. If someone wants to drink water every day, they could easily drink one glass of water and call that a success. They could also have a goal of 8 glasses. Specifically identifying the action gives Tim clear understanding of success or failure.

Set a time. When will he workout? Tim didn’t have time for the second day. He relaxed for 3 hours, but could easily have workout within that time. If he said, “I will go to the gym every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday after class at 12:15,” he would have gone to the gym on the second day. It wouldn’t have been time for Tim to relax, because it would have been time to work out.

Set a Location. Where will he workout? In Tim’s case, he wants to work out at the gym. But, say he wanted to create a study routine. He could study anywhere, but is that a good idea? Studying in his living room, at a café, or in the Library are very different. So, if Tim chose the library, he can’t go home and study. To maximize productivity, he commits to the library, and every single time, he goes to library.

Tim’s implementation intention goes as such…

“I will lift weights for my upper body on Monday, lower body on Wednesday, and full body on Friday. I will end each workout with a 15 min cooldown on the treadmill. I will do this at 12:15 in the gym.”

If you understand your implementation intention, doing the work comes easy. Some days you might not feel like it, and some days you might say, “I can skip today. What’s the harm?” No excuses! You know what to do, when to do it, and where to do it.

It is now time to go do it.

Do you have your implementation intention set? Make the plan and write it down.

Now, go forth and create those habits.

Be patient, work hard, and don’t give up

This post has all the tools needed to equip anyone with the right habits of a successful student. Following the process, step by step, someone could create an arsenal of successful behaviors. Remember, the purpose of cultivating positive habits is to create seamless ease with day to day activities. Minimizing stress, fatigue, and wasted time are all necessities.

Be Patient. Habits take time to cultivate. Make sure to completely understand the habit loop. The process of habit formation is so much easier when the cue, routine, and reward are identified. Work hard. Once you have that information down, implement the plan. You didn’t go through all of the steps to only kind of implement it. Don’t Give Up. There will be days and moments you don’t want to take action. Stay committed and power through those roadblocks. If You Fall, Don’t Give Up. There will also be days those roadblocks seem too much to handle. Just because you missed one day, doesn’t mean you can’t pick up right where you left off. Pick Up Right Now. If you haven’t started yet, what are you waiting for? Pick up a habit and take action.

References

Clear, James. Atomic Habits: Tiny Changes, Remarkable Results: an Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones. Avery, an Imprint of Penguin Random House, 2018.

Duhigg, Charles. “How Habits Work.” Charles Duhigg, charlesduhigg.com/how-habits-work/.

Elmore, Tim. Habitudes: Images That Form Leadership Habits & Attitudes. Growing Leaders, 2012.

“Habit.” Merriam-Webster, Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/habit.

“MIT Researcher Sheds Light on Why Habits Are Hard to Make and Break.” MIT News, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 20 Oct. 1999, news.mit.edu/1999/habits.

Neal, David T, et al. “Habits—A Repeat Performance.” Curent Directions in Psychological Science, vol. 16, no. 4, 2006, pp. 198–202.